Mike JohnsonKia Orana, Alistair Te Ariki CampbellKia Orana, Alistair Te Ariki Campbell, I greet you from the land of the living. I bow my head in respect to you and your work. When I close my eyes I see your ‘long pouring headland,’ your ‘smoking coast’ and ‘men moving between the fires.’ I wish I had known you, but then we were different generations, linked only by our sensibilities and our love of language. For me, you were a bridge from my white palangi culture to Polynesian ways, to your ‘plant gods, tree gods, gods of the middle world...’ I sank into your ocean. I met you in the street one day a year or so ago, but I doubt that you remember. I was passing the Auckland Central Library when I noticed a battered old aluminum book case stuffed with books. Giveaway books. The library was having a purge. And there I found a jewel, your novel, The Frigate Bird, published by Heinemann Reed (who longer exist) in 1989, with an introduction by Albert Wendt who described you as ‘a kaumatue in Pacific writing.’ I could feel your presence, hovering around me, you clinging to the inside of a coconut shell, your Avaiki, your shadow in the impossibly long night, and I shivered. Dead men tell no tales, they say, but that doesn’t apply to writers. Writers can be the dead talking. Reading from T he Frigate Bird then, standing on the Auckland street with people from all over wandering by, I was listening But what was it doing, discarded on the street, lying sideways like a home- less person, this precious piece of heritage? Later I was told there were ‘surplus copies’ that needed discarding. Nowhere to house them. I could hear your voice telling me that a culture that can’t house its books can’t house its people either, and that is already true. We have ‘surplus people.’ It was Heinrich Heine, in the early 19th Century who observed, ‘Wherever they burn books, in the end will also burn human beings.’ Perhaps we can reformulate Heine’s observation into its prequel, ‘Wherever they discard books, in the end will also discard people.’ And that is coming true too, my friend. More and more I see discarded people lying on pavements with no one to come and give them a home, as I did with your novel. Your discarded The Frigate Bird sits in my book case, and is given due respect as a taonga. No longer discarded, but what about the homeless who also cluster around the library? Who is around to treat them as a taonga? Recently Bill Direen contacted me, and told me how many thousands to books have been shoveled into the fires of oblivion. I daren’t think of how many. Whole sections of our culture and cultural memory pealed away. Burnt or pulped. The bleak logic that drives all this would have been alien to you, I think. Cost cutting, space cutting, human cutting. I see your ‘leaf-green/Bodies leaning and talking with the sea behind them...’ and I think of that dusty concrete expanse with its sad old bookcase and its discarded books. So Aere Ra my friend, go well in your chosen ocean. One way or another, your words will live after you. Your guardians are on hand. Waiheke Island, June 2021 |

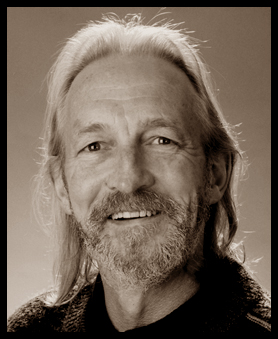

Mike Johnson is a writer 24 books to date, of fiction and poetry. Note: Alistair Te Ariki Campbell (1925–2009) was a New Zealand poet, playwright, and novelist. His father was a New Zealand Scot and his mother was a Cook Island Maori from Penrhyn Island.